CRAFT is a reader-supported email newsletter about the nuts and bolts of fiction writing and the world of publishing.

Dear friends: this is a repost from November 2023. I definitely caught something from the conference I was at last weekend and need some time to recoup. To anyone who is newly following this because you saw me at Hamptons Whodunit, welcome! This is a good example of the type of really detailed craft pieces I write.

Welcome to the third in a series of articles on whether or not more chaotically oriented writers could become more organized, at least with respect to plotting. I wish plotting was talked about in writing or talks about craft, because there’s a clear mismatch: plot is what readers frequently talk about a lot when talking about if a book works or not. (Not the only thing, but a main thing.) I hope that you are able to take something from these articles that you can use for yourself.

I wrote my second novel a little differently than I wrote my first. Never Saw Me Coming is a mystery that is intentionally rapidly paced, and while there is sort of an A plot and a B plot it’s still pretty linear. A Step Past Darkness was different in a lot of ways, so I approached it a lot more methodically—as a writer, I tend to feel more like an architect and less like an artist, and I was very, very concerned about time. Authors have all the time in the world for first novels. You can take ten years to write it, then go through a two-to-three-year agenting and submission process, then your baby is out in the world. The problem with sophomore novels is that many times they are sold on proposal. Which means you turn in a proposal, rather than an entire novel, then sign a contract saying you will get an advance in exchange for writing this proposed novel then that novel is due in a year. This, I suspect, is why many second novels suck: authors were in a hurry to write them under deadline. I was terrified of this happening to me, which is why I took my time, despite feeling anxious about the gap from 2021 to 2024 for my having a book out. I also felt like I wanted to write something more impressive than my first book. NSMC did well, but instead of taking that as a compliment, the spectre of previous success turns into a ghost hovering in the background asking, are you going to do better, or are you going to disappoint people?

How To Write Under Contract And Hopefully Not Fail.

I more or less entered into a contract for A Step Past Darkness with my publisher on February 1, 2022. I knew this was going to be a very big book: length, six POVs, complex dual timeline. Writers break deadlines all the time, but breaking deadlines is something I was not going to do short of a major life emergency.

In the summer of 2021—as we were doing a lot of publicity for the launch of NSMC—and into that fall, I plotted out ASPD in its entirety before I even wrote a word of text. I spent the first month only working on character, figuring out who they are, and their relationships to each other. I have written about how I do that in this post:

Then I wrote chapter by chapter summaries which formed a detailed outline. This outline was for no one but me. It was more detail than “John goes to the store and runs into Mary” but short of actual prose. It was detailed enough that the summary itself was about 23k. Here’s an example from Chapter 1 “Zachary Springsteen—whom everyone of any importance refers to by his childhood nickname, Blub—is the deputy sheriff of Wesley Falls, a small idyllic town in Pennsylvania somewhere between rural and suburban. A place where there is no McDonalds because the town thinks it would be a corrupting force, but maybe there’s more suicides than natural. Blub takes a rookie cop with him to pick up Jia, a mysterious woman that Blub claims to have known from high school, from the train station, where she is arriving from Philadelphia.” An outline doesn’t have to be terse: for me, when I’m outlining, I feel the same sort of creative spirit I do when I’m writing prose. A more detailed chapter by chapter summary allowed me to have more of the feeling of the chapter than just “Blub picks up Jia from the train station.” This blueprint did not have 100% of the plot points from ASPD, but I would say it had about 90%, with most of the stuff still hiding in fog being the very last few chapters.

I like to think of these detailed plot summaries as the corollary to how chefs use mise en place. Because if meals are cooked to order, they are not going to start chopping onions once they get your order, but before the restaurant opens are going to prepare all the ingredients so they are ready to go quickly.

Mise en place photo by Rudy Issa on Unsplash.

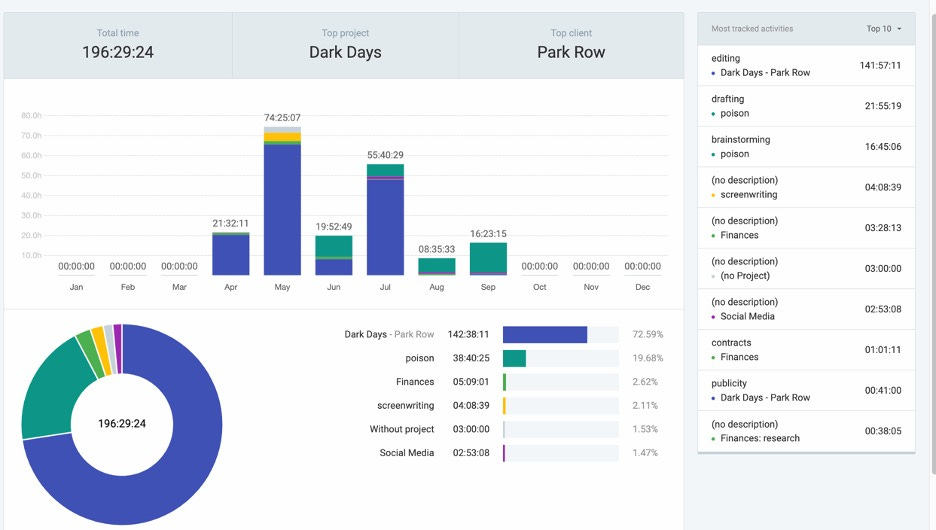

I wrote A Step Past Darkness over the course of 2022 at about a rate of 15k a month. 2023 is when I started using Clockify to track how much time I spent doing various writing things. I did this because I wanted to know the relative cost of time I was taking to do writing things, including actual writing, publicity, social media, etc.

So for context, I handed my manuscript in in late December of 2022. First, see the blue bar in April? (Dark Days was the working title of ASPD). That entire bar, 21 hours, was time I spent thinking about ASPD without writing in the traditional sense. My editor had given me her first round edits in April. These were not line edits, but substantial “this major thing isn’t working” type edits. I would say this was a request for a 40% rewrite. All of those 21 hours were spent just thinking about plot—I did not write any prose. This was time I spent writing post-its and moving them around on my desk and walking around with a quizzical look on my face and working on long documents that that reasoned out plot options.

The end product of those 21 hours was a few different, very detailed documents, some of which I never showed to anyone. They were things I needed to do for myself. This included:

A timeline of what happened to the characters in 1995 when they were kids

A timeline of what happens to them in 2015

A timeline of everything the murder victim did the day they died

The life story of the “villain”

A two-columned document where the left side had the basic points of each chapter, and the right had what would change in the new version of that chapter

A Word doc that was most of a new proposed 2015 timeline summarized

I had a lot of reasons for wanting to be meticulous about this. For one, I didn’t want plot holes or things that didn’t line up temporally. How can your detective solve the murder if you the author don’t know what the victim was doing the day of their death? Also, because it was dual timelined I needed to keep track or who knew what when which wasn’t easy.

I only gave the last three documents to my editor and agent (this was after talking through it with my squad—when it comes to logic, you always need a squad to check your work.) By the beginning May everyone had approved my plan and those some 65 hours in the chart in May was me actually rewriting the text. The other big bar in July was round 2 edits, though honestly a huge chunk of that time was me cutting a mid 500s page book to “under 500” (ie, 499 pages). I had to do this with surgical line editing and killing many, many darlings, which was incredibly time consuming because I wanted to save what had to be saved while making things as tight as possible while still making sense.

So all in all, I was able to write a 180k novel in about a year and a half. (before you scream, the final novel is not that long). I don’t know what readers will say and critics have yet to get their hands on it, but I personally feel it is a stronger book than my first book, and a more complicated one. So I will call it a success regardless. A few lessons I learned:

Blocking time off was extremely critical. If I did not take a bunch of leave in May, meeting deadlines for our desired print date would have been impossible. I took my deadline seriously but am also fortunate in that I tend to have a good sense of both how long it will take me to do something and how long a book is before I write it.

While it is hard when someone says “you need to considerably rewrite huge sections of your baby,” I learned that I actually liked the sort of problem solving involved in trying to fix the various puzzles associated with plot. It reminded me of the feeling I used to get in lab during grad school. These were typically sessions where we had to do something like, How can I measure X without the participants figuring out that that’s what I’m measuring?

Well, now that you’ve seen how the sausage is made, if you would like to see how the final product came out, here it is:

There's something sinister under the surface of the idyllic, suburban town of Wesley Falls, and it's not just the abandoned coal mine that lies beneath it. The summer of 1995 kicks off with a party in the mine where six high school students witness a horrifying crime that changes the course of their lives.

The six couldn't be more different.

Maddy, a devout member of the local megachurch

Kelly, the bookworm next door

James, a cynical burnout

Casey, a loveable football player

Padma, the shy straight-A student

Jia, who's starting to see visions she can't explain

When they realize that they can't trust anyone but each other, they begin to investigate what happened on their own. As tensions escalate in town to a breaking point, the six make a vow of silence, bury all their evidence, and promise to never contact each other again. Their plan works - almost.

Twenty years later, Jia calls them all back to Wesley Falls--Maddy has been murdered, and they are the only ones who can uncover why. But to end things, they have to return to the mine one last time.

I enjoyed reading about your process. Much of it feels familiar. I've gone from plotting to pantsing and back to plotting. I realized I prefer knowing what's going to happen next as I'm writing, or at least having an idea, even if the details change as I write.