CRAFT is a reader-supported email newsletter about the nuts and bolts of fiction writing and the world of publishing.

Friends: this is a slightly updated version of a post I originally wrote in 2023. I am working on a post that looks at author advances vs sales but couldn’t scrape it together in time as I have a rather nasty cold. Here is another data-heavy post I happen to love.

Authors are urged to use social media to grow a following to sell books—this seems like common sense. More popularity—> more book sales. Midlist authors (those who are not lead titles) feel even more pressure to do so, making up the difference in marketing that lead titles are getting that they are not. But there’s a push-pull here between publishers and authors. For publishers, it’s simple: authors should be on social media because authors posting on social media is free—it costs publishers no money or effort. It’s more complicated for authors: investing time in social media might sell books or it might not, but we know for a fact that it takes time away from writing, and there’s a whole host of negative things associated with social media (becoming addicted to the clicks, parasocial relationships, harassment* and rude behavior from users, etc.) *look what just happened to Ali Hazelwood!

Publishers will always be incentivized to tell us to get on social media, and some authors might feel pressured to do so even though they hate it and are not even sure it moves the needle. We have all seen books shoot to bestseller status when they get a lot of love on TikTok. This has been true for both traditionally published books and self published ones. So clearly it works sometimes… but it seems like most of those viral passionfests are driven by BookTok users, not the authors themselves. I assume it is easy for publishers to track the direct impact of marketing on sales: they do an ad buy, then look at sales on the week of the ad buy. But authors don’t have access to that kind of data (exception, I think, if you publish via an Amazon imprint). Authors only have access to quarterly sales data of their own books from royalty statements, which can’t realistically be used to measure something like “the impact of social media.”

Does literally anyone know the answer to the question “does social media sell books” because it seems like everyone is sort of shrugging…?

I remain skeptical. It made a pretty big splash when Billiee Eilish—who has 97,000,000 Instagram followers and 6,000,000 on Twitter—released a book and a disappointing number of people bought it. But she’s a musician, you might interject, people who listen to music might not be the same as people who buy books! (A fair argument, but Britney Spears and Barbara Streisand were both on the NYtimes bestseller list at the time of writing. So maybe predicting sales from blunt equation like popular=good sales is stupid..?) I’ve also observed authors who have pretty strong social media followings, some of whom are selling a lot, and some of whom sell more modestly than me. Some people are good at making attractive content that people want to look at on Instagram, and maybe what that number best represents is how good you are at Instagram, not how well you sell books. (Let alone that some people on Instagram do a lot of mutual following- sometimes to the tune of thousands.)

An attempt at data analysis

I’m going to try to use data to answer these questions rather than a handwavy “it’s probably good and it can’t hurt.” For those of you who don’t know, my background is in social psychology, and I leaned heavily into the quantitative side of things (ala, How do we measure things that are hard to measure? How do we design an experiment that gets at the phenomena we are interested in without adulteration from other effects?) I don’t think it’s acceptable to believe things to be true without evidence to support it. However, it does make me wince a bit to publicly produce something as methodologically imperfect as I’m about to but 1) i think it’s better than nothing and 2) see my discussion of P&Ls below…. You’re about to see a lot of caveating, because this is a really hard topic to study, and the data I have access to is limited. I’ll talk at the end about what an ideal analysis would look like.

Books: I used a list of 100 books that were published in 2022. I picked 2022 because 2021 was a bit too touched by the pandemic and 2023 [wasn’t over yet at the time of writing.] I also threw my own book in there (despite it being a 2021 book—sue me) because I have access to the real sales data there as a comparison point. These books were taken from a list on Goodreads of “Best books of 2022.” This gave a good smattering of books across several different genres: literary, mystery, romance, fantasy, etc. Because of how lists work on Goodreads, this still allowed books that had more modest sales to be higher up on the list (because order in the list was determined by people voting books onto the list, not sales or number of ratings or reviews). If an author had more than one book, I only selected the first book (because datapoints should be independent). Colleen Hoover and Ana Huang had more than one book on the list, so any book after the first was struck. I struck Robert Galbraith from the list because some people might be unaware of his true identity and there are two associated Instagram accounts. I think there are two authors on the list where the “author” is actually two people writing under one pseudonym- I allowed for that.

Followers: This was a simple count of followers on Instagram, rounded. Some authors do not have Instagram accounts, so they scored a 0. (Of course, I understand that some authors are not on Instagram but are on other social media platforms, such as Stephen King.) This makes this study focused specifically on the relationship between Instagram followers and sales.

Sales: This is the hardest. If you are not an author, you might not be aware that getting this data is surprisingly difficult. Basically, the only way to get accurate sales data is from the publishers themselves and they’re not going to give you their data. An author can periodically get access to that data from their publisher via royalty statements. But I was not about to ask 100 authors for their private data, and even if they were willing to give it, odds are people would be reporting different things accidentally. There are some ways to access incomplete data, which is what I did. I used sales data from a commercially available database that collects data from a major book distributor which included a number of warehouses in several US states. To be clear: this is an underestimation of sales. I know this from both common sense and from looking up my own book in the database and comparing it to the actual sales number. The purpose here is to use the same imperfect ruler to measure all the books. To explain more fully, if you wanted to weigh things, ideally you would have a scale that accurately and consistently measures weight. But say you have a scale that measures a 150 pound person and says they are 100 pounds. Then we weigh another person who is actually 200 pounds and it says they are 150. So it’s 50 pounds off—this doesn’t matter if the only thing we want to know is if person 2 weighs more than person 1. In this dataset, the sales number for each book included print copies, audio, ebook, library copies, and CD audio—again, incomplete data, but at least including multiple formats.

Analysis!

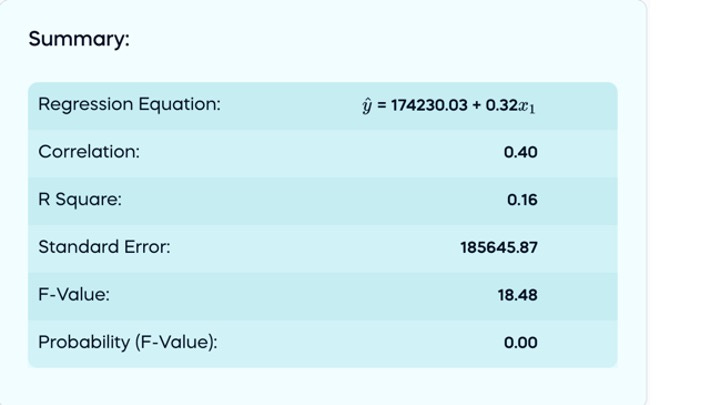

I did a regression analysis of followers and sales. Basically this is a statistical method of trying to determine to what extent Instagram followers is associated with increased sales.

This analysis is saying that yes, follower count is associated with sales (ie, it is statistically significant). The correlation here is .4—as someone coming from a behavioral science background, and r of .4 is pretty strong! The .32x1 at the end of the first equation means a slope of .32— indicating that for every increase of 1 Instagram follower, this increases sales by 32 cents. Wow! case closed.

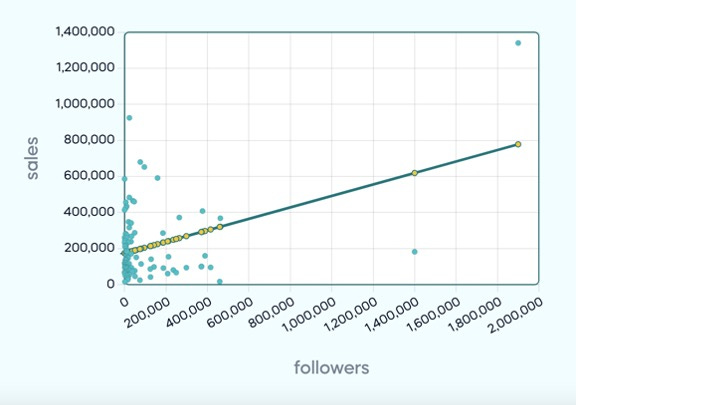

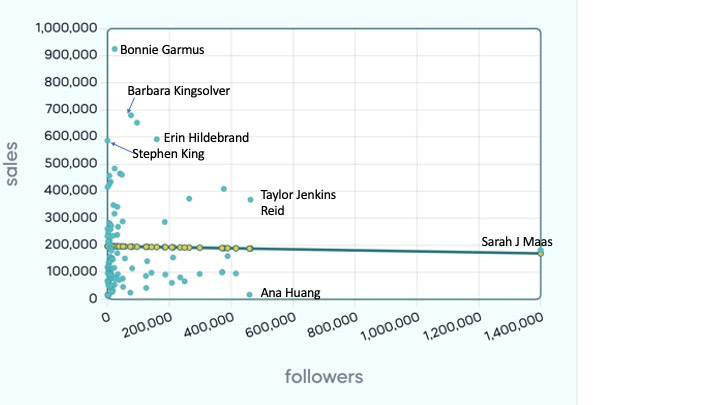

Except… Look at the chart below. Don’t be distracted by the sales numbers—just remember that they represent the lower end of what the actual sales of what any particular book could be, and it is the relative difference that matters. So the former grad student in me would look at this and my eyes would instantly be drawn to that point all by itself in the far right corner. That is Colleen Hoover. (Reminders of Him, specifically). She is what we would call an outlier. What you’d typically do then is try running the analysis again without her data to make sure that she isn’t having undue influence on the results. This is because of your entire effect is driven by one or two people, there probably isn’t an effect.

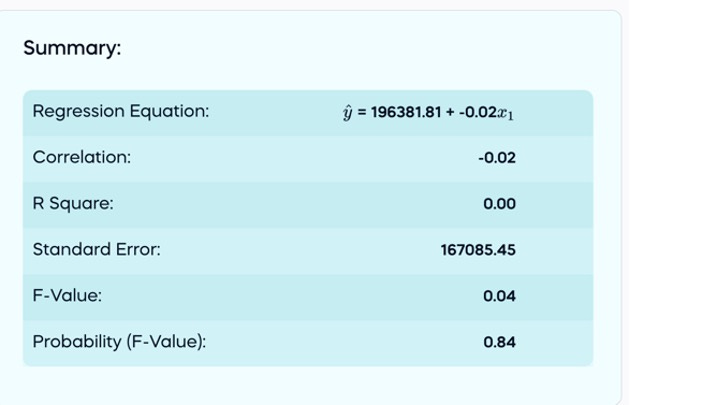

These are the results without Colleen Hoover.

That probability value is basically saying that there is no meaningful relationship between Instagram followers and sales. Look at the graph without Colleen Hoover below- when there’s a relationship between two variables, you don’t see a flat line, you see a line going up, or a line going down, or a line curving in a meaningful pattern. A straight line is what you see when there is no meaningful relationship between X and Y.

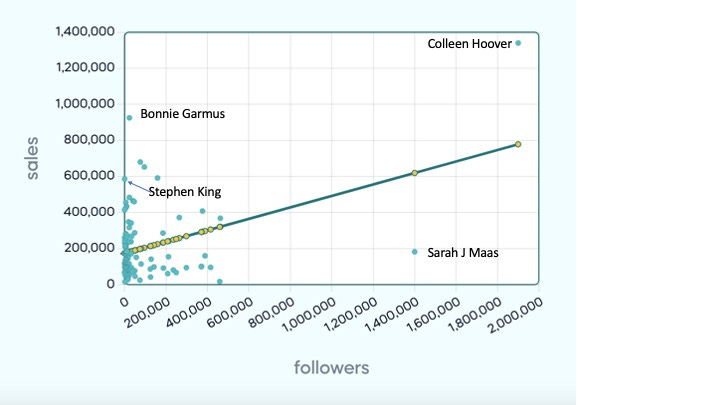

I went back and labeled some of the datapoints on both of the graphs.

If you look at where Colleen Hoover is on the graph, she’s is where publisher’s ideal would be: a nearly 1 to 1 relationship between followers and sales. But Colleen Hoover isn’t normal. While she had fans before, her blowing up on TikTok had such a massive impact on her sales. Also consider how the Hoover phenomenon played out: for whatever reason, a few people on BookTok were talking about her books at the same time. Then others started to read them and posted their reactions. Then this kept happening over and over. But—and please someone correct me in the comments if I’m wrong—Colleen Hoover’s own behavior on social media wasn’t the origin of the BookTok frenzy. Bottom right, that is House of Sky and Breath. We all know Sarah J. Maas sells really well, but that one particular book in the past 2 years has not done as well as Reminders of Him. Maybe this is unfair because Reminders is a standalone and House is the second in a series? But 1) if you took her out of the data, I don’t think the line gets back its slope and 2) if social media following creates sales, it should do so for series as well. Look at the below chart where I added some books.

Garmus’s enormously popular Lessons in Chemistry sold really well, though she doesn’t have a ton of followers. It was just a good book that sold itself and importantly, it was a debut novel, indicating that sales were not driven by a fanbase from previous books. Stephen King, Erin Hildebrand, and Barbara Kingsolver are all powerhouse authors with either low or no followers on Instagram. Ana Huang (another viral TikTok pick) is interesting because she has about the same number of followers as Taylor Jenkins Reid, but TJR sold better. Let’s look more closely at the 10 people with the lowest follower count.

Fairy Tale, Stephen King, No instagram. King doesn’t need social media to sell books—he’s a cultural icon. While he does have quite a following on Twitter, I think these are people who are already fans, and if anything, it’s more likely to make them buy books he recommends, not his own books. (Honestly, I follow him on Twitter to look at pictures of his corgi, Molly the Thing of Evil.) [I’m aware king has left twitter at this point, as most of us have]

Horse, Geraldine Brooks. No Instagram. Brooks is a 68 year old Australian-American author. Horse is 6th novel since 2001, and her second novel, March won the Pulitzer Prize.

Marriage Portrait, Maggie. O’Farrell. No Instagram. An Irish author, and this is her next book following the very popular and critically acclaimed Hamnet.

Trust, Hernan Diaz. No Instagram. As far as I can tell, he’s not on social media at all. (Baller). This is an author whose debut novel was a finalist for the Pulitzer and the PEN/Faulkner award and then his next book went on to win that Pulitzer. (I’ve gushed about Trust elsewhere.) This guy is in a class by himself.

Lapvona, Ottessa Moshpegh. No Instagram. Moshpegh’s entire Thing is that she is weird. I don’t even think she has a website. She does have a cult following though.

Nettle & Bone, T Kingfisher. No Instagram. This is the pen name for Ursula Vernon. She writes both adult and kids books, both of which have been selling solidly for a decade.

Peach Blossom Spring, Melissa Fu. This is a debut historical fiction novel. Her sales were comparable to two other authors that had followers in the 200,000-250,000 range while hers was only 1400.

Never Saw Me Coming, me. I’m a nobody with a small number of Instagram followers (1400) and I rarely post. This was a debut novel. It was a lead title, which meant it probably got a good amount of marketing, though I have no idea how much. I was not a major book club selection. I have heard both “I see your book everywhere on social media” and “people are sleeping on this book.” It was critically acclaimed in trade reviews and got an Edgar nomination, had strong library support, and from what I can tell, good word of mouth.

Hester, Laurie Lico Albanese. The author has a few other books, but this historical fiction hit the biggest- I would guess because of the premise (It’s a prequel to The Scarlet Letter.)

Hunt the Stars, Jessie Mihalik. Space opera with romantic vibes, first in a series, and the author has several series.

So you’ve got powerhouse authors who don’t need social media, people with established credentials, and debuts—who you’d think would need social media, but do they even really have the time to create a following because why would you follow someone who is a nobody unless you’ve already read their book?

I reordered the list by sales, looking at 10 books that performed similar to mine in sales (five above, five below). This group included both people like me who had very modest numbers of followers and some more established authors you’ve heard of in the 300,000 range.

But isn’t this study significantly flawed?

Yeah. But remember that part of the DOJ vs. Penguin/Simon & Schuster antitrust lawsuit where publishing execs admitted that P&Ls were pulled directly out of editors asses? A P&L is a document that will be made up for a potentially acquired book, where the editors will guess how much money the book will make based on some data. Acquisitions boards will look at this data when making the decision about whether or not to acquire a book. Some of the data in these P&Ls is very much real—like estimates of how much it will cost to print the book. Other stuff I find a bit more suspect, like trying to estimate sales based on comps. That’s like saying “because this high school senior is the same weight and height as LaBron James, we estimate he will score the same number of points.” Sometimes a person can’t be boiled down into a statistic. Sometimes people who don’t look like they’re going to be LaBron James turn out to be LaBron James. Also? As far as I know and please correct me if I’m wrong in the comments, P&Ls are made by editors not—as I once naively thought—data scientists. Not dunking on editors (no pun intended?)—the thing I’m dunking on is making life-altering decisions based on shoddy data. At least my shoddy data isn’t going to make or break someone’s career lol. And we know that acquisitions boards have turned down books that went on to sell millions of copies. (What I would like to know is if the method of calculating P&Ls is actually adjusted based on previous P&L success or failure. Apparently they are very secretive about how they are calculated.) [the post I am doing next week is looking at author advances and how well those authors actually ended up selling—sort of a crude measure of “how well did the publishing company do at predicting if this book will be a hit.”]

If I wanted to do this study for real, I would probably take authors publishing in the same year and include the following variables: age of author, gender, advance size (as a stand-in for marketing budget), genre, age category, if it’s a debut or not, number of previous books published, if it’s in a series, and follower count for Facebook, Instagram, X Twitter, TikTok, and Goodreads, with all those predicting sales for the first year. It might be the case that social media only drives sales for women authors in romance or something, or that there is no relationship for some platforms, but is for others. (Am I going to do this study for real? No. It would be a lot of work. But I’m happy to do other similar quick and dirty convenient data analysis when the data are available.)

An alternative hypothesis…

What if social media followings don’t drive sales, but sales drive social media followings [if the author chooses to be on social media]? This strikes me as eminently reasonable. People read Colleen Hoover, loved that first book, then chose to follow her. If I follow CoHo, I will be alerted when her next book is coming out, and maybe I will buy that. So social media could help there… but what if I was going to find out about her book anyway?

So if you are an author looking for an excuse to get out of stressing about social media, I’ve given you one. Sadly, it seems as if the trend is towards the even more intensive (in terms of labor) platforms. Twitter was pretty easy because it was just about shooting off a sentence now and then. (I actually liked it before it became a cesspool.) Instagram requires you to be reasonably good at photography and/or photo editing, to plan out posts, to arrange things such that they are physically attractive. I find it kind of exhausting because I’m a writer—I’m not good at visual aesthetics. But TikTok is the Thing that everyone is talking about, but video content is significantly more labor to create, and people keep chasing virality as if it is something that could be tamed. But instead of asking the question “how can I create TikTok virality in order to sell books?” why aren’t we asking the question “what is it about Colleen Hoover or Song of Achilles that makes them go viral?”

Thumbnail icon by Alexander Shatov on Unsplash

This is brilliant, as always! I'm looking forward to linking this in future posts about social media and the author's life.

Damn, what an analysis thank you. Also, I often find it boils down to a ratio. If 1-3% of a person’s follower count converts to a sale, that’s the demand for such high numbers.