CRAFT is a reader-supported email newsletter about the nuts and bolts of fiction writing and the world of publishing.

1/13/25 All: I hate that my 100th Craft Post is a repost, but to be fair, it was actually last week that was the 100th post, so this is the 101st post. I’m moving tomorrow, to my midlife dream home, somewhat subsidized by writing money. (stay tuned to my Instagram for “hapless person doing DIY and decorating”) I do, however, love this particular post, which was from my first month of Craft, which means most of you have not read it.

I’m unapologetically a writer who’s focused on character—it’s always going to be a number one priority. Because my second book features an ensemble cast, I really wanted to make sure I got character right—in fact I spent a month alone developing characters before writing a word of the book. A Step Past Darkness, which came out in 2024, has six main characters, and each is a POV character. Ensemble casts are hard to do regardless, but when you have multiple POVs it’s even harder because each POV needs to feel unique. In many ways, Stephen King’s It was my model because he does something really impressive in it: there are seven main characters in that book (at least when they are kids in 1956) yet every single one of them felt fully realized. I understood their inner feelings, their families, their insecurities. In studying the book, I thought a lot about how character is not just who you are—your personality traits, your appearance, your values, etc.—but who you are as a member of various systems. I like to think of this as the fourth dimension of character.

(If you haven’t read my earlier post about making three dimensional characters [below] I would recommend reading it in conjunction with the current post.)

I want to talk about another dimension of character beyond the standard things we typically think about. All people are embedded within systems. If you don’t have this aspect to character, the character feels like they are strangely floating in space. A person is a member of a nuclear family (even if they are estranged from that family), and that nuclear family is part of a broader family tree. An accountant at a corporation is one of many workers. A friend group is a web. A woman married to a man is part of a dynamic couple where people play both stable and unstable roles.

As someone who’s read a lot of mysteries, I can’t tell you how many I’ve read that involve a woman with a husband who does a lot of mysterious and often bad things to her. And I’m always thinking, Where are this woman’s friends?? Because if it were me, the second I said, “Well, I called the number he said was his fishing buddy, and a woman picked up and hung up on me when she heard my voice, but my husband said I was confused, so I guess he’s right.” My friends would be giving me bombastic side-eye and no way I’m walking out of that brunch without having undergone an investigation so thorough it feels like a colonoscopy. The reason why cardboard cutout characters are often isolated in bad books is to prevent any questioning of illogical things that happen in the book. (This is also the type of MC who keeps making catastrophically stupid decisions over and over to serve the plot.)

Work and career are important dimensions of identity

In a lot of books, it feels like the person’s profession is just something the author slaps on because human beings need to have professions. Nonspecific Architect is a common one, as is “Businessman,” or Doctor. (Why are there never any claims adjusters or scrum masters in novels??) At least in America, profession is a significant part of a lot of people’s identities. Sometimes it feels really hollow if we are just told that someone is a teacher and we see one stiff scene of them at school, probably for the sole purpose of showing how kind and caring they are. But if we fully included who that person is in their profession and however that system works, we feel more of a sense of reality. (I’m incidentally also not a fan of when a profession is used as shorthand for personality. Not every teacher is kind and caring and loves children. Not every professor is smart.)

Let’s use me an example: grad student. (well, former grad student). How I act as a grad student is of course colored by who I am as a person: I’m analytical, creative, but also impatient and rather snarky. But who am I as a grad student embedded within the community of grad students? I was a social connector because I was in the Social Psych program but I lived with someone in the Clinical program, so I branched that divide and was also good friends with different cohorts. I was a methods person, so I was aggressive when people presented in lab (maybe to the point of it being offputting) but I was also good at statistics so people came to me for (free) help, which I liked doing. I’m a weird combination of lazy and efficient, so I worked short days and then spent my free time goofing off with people who were not workaholics. People thought I was smart based on things I said but not based on what I did in terms of publications, because I never had the patience for academic publications, which also meant I was not well known in the broader community of social psychologists outside the department. As a result, I was well liked and seen as interesting, but was not particularly good at being an academic, though whether or not people thought I was smart was independent of that. All of that is a lot more information than just “grad student.” If I wrote a character like this, a reader who had been through grad school might nod and think about how there were all types of students in their program.

In a previous post on dialogue, I referenced three characters who are in the current book I’m writing. They all have the same profession: musician. (They are all musicians in the same band.) A lazy writer would just use the label “musician” and maybe tack on a scene of them playing music once, but never consider who are they as musicians and how do they fit in with the broader system of musicians. These three guys, Cyrus, Owen, and Klaus are the core of a band. Klaus is a reliable but impatient person who is a drummer but doesn’t do a lot of songwriting himself. Cyrus is a peacemaker who often smooths tension between Owen and others because he hates conflict—and he also does some writing. Owen is generally a nice person, but when it comes to being in the studio, he’s sort of an asshole who thinks he knows better than everyone. He does the vast majority of writing, and has the implicit assumption that he can break a variety of rules because he’s talented. This is a system that you could see as stable sometimes, unstable at other times—this gives you more room for tension as a writer and is more interesting for the reader.

Friendships are complex networks

It bothers me when characters don’t have friends—unless the point is that they live in total isolation—because they have no one to bounce ideas off, no one to rely on for emotional support. It reminds me of how in reality TV shows like The Bachelor or Survivor the contestants are often emotionally or physically starved in order to make them more emotional and dramatic. But if we are talking about a novel and not reality TV shows that nearly kill their contestants.. why don’t you just do this the honest way? Oftentimes we are just presented with one person and told “this is THE friend.” The sassy Black girlfriend. To be fair, sometimes it’s a gay guy! But very often it’s a person who seems to have no life of their own and no thoughts other than whatever drama is going on in the main character’s life. But thinking of the dyad of a friendship, who is your main character in the dyad? Are they the one who listens more, or talks more? Who calls who more often? Is one jealous of the other?

One of the best fictional friend dyads I’ve ever seen is Elena Ferrante’s My Brilliant Friend series (the Neapolitan novels) which follows two Italian girls from childhood into their 70s. Their relationship has so much depth and is capable of being stretched and shifting over time. The initial setup is that the first person narrator, Elena, believes that her friend, Lila, is smarter and more talented than her. Lila, we find out later, may not agree. Both girls are poor, but Lila is significantly poorer and her life takes a very different course as a result. Class and money differences create tensions between them, as do Elena’s feelings of being less beautiful and intelligent, or the fact that Lila seems more indifferent to norms in some ways. These books are not super dramatic in terms of the actual plot points, but most people who like them describe them as absolute page turners. (I obsessively devoured all four books within a month). This was fundamentally driven by the sheer psychological depth of this relationship. Which is also why I found it psychologically devastating when the book ended.

I love ensemble casts, and done well, they are incredible. Done badly, each person has a couple characteristics that distinguish them—one is smart, one is boy crazy, one is a minority cough cough—and we are told to believe that the group is super tight. But groups are more complicated than this. I was part of a close trio of friends once, and have been since the late 90s. In my mid20s to 30s we basically hung out every single weekend. However, before then, I was off screen for six years when I was living far away for grad school. Sometimes when we hung out, I felt I was missing some intimacy and shared stories that occurred while I was gone. Of the three of us, two had similar family conflicts. Two of us loved reading. Two of us were white. We would play different roles at different times. “They were friends” doesn’t cut it. Think of describing the moon. Then think of it rotating the Earth, then think of it as part of that dyad orbiting the sun. A woman is a person. She’s also a wife—does she act or seem different when with her husband alone? Who are they when they’re out together?

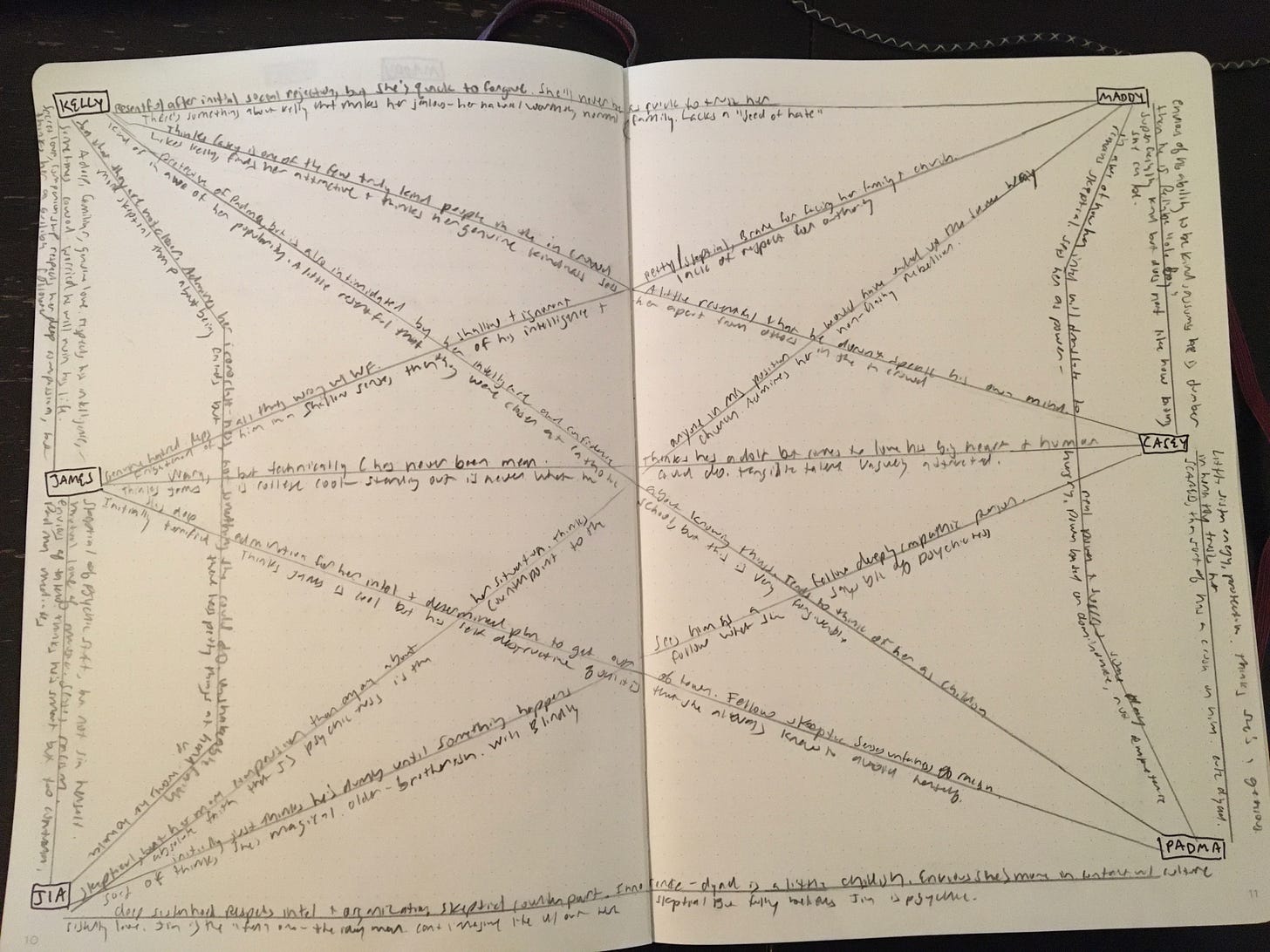

When there’s a large number of characters, I like to draw a relational map (below- it looks like some sort of Satanic ritual..)

Each character is a node. Then I have to figure out every permutation: how does Jia think/feel about Padma, and how does Padma think/feel about Jia? Then I did this for each pair. Then outside of dyads I thought of other combinations. Sometimes when there’s a friend group, we are presented with a highlighted dyad: Barbie and Ken are the “leaders” and cool kids of the group… then everyone else is just sort of … there. Make this more dynamic and it has more of a feeling of realness. Within the above group, there are two sets of best friends. There are three people with “good” families, three people with “bad” and this dynamic plays out into how they interpret conflicts or who they can trust. There are four girls, who form a natural grouping, which force creates a dyad of two boys who have nothing in common but their gender (but it’s fun to see them together). Each person is in a different place on a spectrum of spirituality (this is because religion is a key theme in the book).

Family systems

I am very interested in Family Systems Theory, not just as a writer but as a human person moving about the world. In short:

Bowen family systems theory is a theory of human behavior that views the family as an emotional unit and uses systems thinking to describe the unit’s complex interactions. It is the nature of a family that its members are intensely connected emotionally… Families so profoundly affect their members’ thoughts, feelings, and actions that it often seems as if people are living under the same “emotional skin.” People solicit each other’s attention, approval, and support, and they react to each other’s needs, expectations, and upsets. This connectedness and reactivity make the functioning of family members interdependent. A change in one person’s functioning is predictably followed by reciprocal changes in the functioning of others.

If you want to go super deep on Family Systems, you can read more here.

People who are interested in Family Systems will map an entire family, ideally going beyond just the nuclear family. Maybe overkill if family isn’t important in your book, but absolutely worth doing if you’re writing an intergenerational saga. (I once did this for Flowers in the Attic when I was trying to explain the familial complexities to a friend which is hilarious.)

Here’s a really simple example of two nuclear families adjoined by one friendship (next-door-neighbors).

The family in blue is broken. The thickness of lines indicates the strength of relationship. James had a strong and positive relationship with his mother, but she died, then his father left, cutting off their relationship. (What impact do both of these things have on him?) He then lives with his aunt—who is not a great guardian, and who herself did not have a good relationship with James’s mother. Aunt has a live in boyfriend who is a piece of shit. So, lots of negative relationships here. Kelly’s family is intact and generally functional—I didn’t bother giving all the lines +s because they were all the same. There’s four important dyads: Kelly’s closer to her mother than her father. Her parents have a good marriage, so they are close. Her two sisters are so close in age that they are referred to as “twins” when they aren’t really. Lastly, James and Kelly are so close (best friends) that he is like an adjunct member of the family. But how he feels about being an adjunct member—? it has its benefits but he has a lot of pride. He’s sort of a delinquent but deep down, unconsciously, he sort of craves the normal structure that basic parents would provide.

Same trope, different story

I’ve gone on for a while about character in two pretty long posts, so I may lay off that topic for a little but, but I want to talk about an interesting reading experience I’m having right now. I’ve somehow managed to be a mystery writer who’s never read Dennis Lehane until recently, which is embarrassing. I recently went on a binge at a bookstore and happened to buy Since We Fell. I’m not done with it yet (so no spoilers!) but am really liking it. Little did I know that it contains two tropes that I normally hate in mysteries/thrillers: an agoraphobic woman married to a mysterious man who appears to be lying to her about some basic stuff. I can’t tell you how many books I’ve read (or tried to read) with these tropes that I have disliked. Usually the woman is an idiot. Usually the agoraphobia—or whatever psychological hangup—solely exists for the purpose of a plot device. The woman marries the mysterious man because… reasons… and doesn’t ask the right questions because, well, she’s an idiot. But I have no problem with these exact tropes because of how well Lehane writes character and writes on the line level. We see how Rachel develops agoraphobia and its entirely reasonable—she has seen some shit in Haiti and the reason she has seen some shit in Haiti is because she has a real profession she cares about. We see, in a complex way, how that agoraphobia affects her life, her personality, her career, her marriage. It’s also never used as a clumsy clutch to facilitate some plot point. (“I can’t call 911 because the phone fell outside my front door!”) Unlike 100% of these books that I’ve read previously, I 100% believe and see how Rachel fell in love with her husband. (Again, not done with the book, but I think he does love her back in some weird, complicated way.) But we see how her romantic relationships are informed by the family system she grew up in.

Consider looking at whatever you’re working on right now and think about whether or not you’ve considered some of these dimensions, and if those dimensions differ across characters. In what ways can you make them richer? Because what makes characters feel real is often their strangeness, that they hav a unique combination of attributes that makes them them and not someone else—this is what makes them memorable.

Coming soon: Can I turn a pantser into a plotter?

Photo by Benjamin Behre on Unsplash