The dual-timeline structure is really familiar to readers, and is especially common in mysteries. While my first novel had a traditional timeline—in fact there is barely even a flashback in that book—I knew that I wanted my second novel to be dual-timelined, but wanted to avoid a lot of the pitfalls of that type of plot structure. When done well, it’s satisfying, but when done badly, it can feel hollow, like half the book was pointless. My second book, A Step Past Darkness, is very much an homage to Stephen King’s It and in some ways emulates it’s structure: he makes you fall in love with these seven kids, something terrible happens to them, they split up, then they have to get the band together as adults. But he does this over the course of a sprawling, 1000+ page novel. Could this be done more tightly? I studied what worked well with It and approached structuring my own book carefully after studying what I thought were the primary problems of many dual-timelined books, three of which I outline below.

One timeline is boring. I don’t think I have ever seen a dual-timelined book that did not have this structure: something interesting happened in the past (T1) and people later on are investigating that mystery (T2). (I suppose to not have that structure you would have to have some time travel? I guess The 7 1/2 Deaths of Evelyn Hardcastle is kind of T1 investigating T2?) The problem with this is that readers are almost always more interested in one timeline than the other, and it’s going to be the past, because that’s when the mysterious Thing happened. In some cases, the T2 people aren’t even related to the T1 people in any way, they just stumble upon the mystery. These are the least interesting of these books, I think, because the stakes aren’t high. The T2 storyline is actually just a frame for T1 and I’d find myself skimming through those pages because they were often pretty irrelevant, or I’d just want the tidbits of information (clues) related to T1.

In many cases, authors write really vibrant T1 stuff—often taking place during childhood or young adulthood—and really nail the voice, but then T2 seems stiff and uninteresting. When it’s clear that T1 is where all the action is, why would I be invested in T2 at all? Often T2 serves simply to provide the one final, missing nugget to the T2 mystery. But if T2 fundamentally doesn’t matter… why not just write the entire book in T1?

While I definitely enjoy the 1950s timeline more in It, I’m still invested in the 1980 timeline for a couple reasons. For one, King does such a good job making you invest in the seven main characters when they’re 12 that you end up being invested and eager to find out who they are as adults. One of the best scenes in that book is when, after the adults are called back to Derry to face Pennywise, they have one fantastic reunion dinner at a Chinese restaurant (never mind that it ends with horrifying fortune cookies)—it was just joyous to see them reunited because I was also interested in their relationships with each other.

When writing ASPD, I tried to deal with the “one timeline is more interesting” problem in three ways. One, accepting that T1 is going to be more interesting. I deliberately had more pages devoted to T1 than T2—it’s the majority of the book. I also made sure that all the adult sections moved at a fast clip. Second, and I hope I did this as well as Stephen King, but I worked hard to make readers invested in the six main characters, which meant spending a lot of time developing them (and their relationships) before I even picked up a pen, and making sure that characterization was really apparent at the start of the book. It had to be a character-driven book: ensemble casts don’t work with bad or thin characterization. Third: T1 has a mystery, and T2 has a separate mystery revolving around who killed one of the six main characters just before the T2 timeline started. They are intertwined, but related mysteries. So it’s not the case that T2 is just about solving T1, but about solving this murder, and doing so will completely solve the T1 mystery at the same time. This wasn’t easy to do. It involved a lot of problem solving and hours spent just thinking about plot to make sure all the pieces fit together. (see this post for more.)

The pacing is off when you flip back and forth between timelines. This is how it’s done badly:

T1 something interesting happens

T1 something interesting happens

T1 something interesting happens

T2 MC moons about “things that happened that summer.”

T2 MC thinks about “the past” without telling the reader what exactly they are talking about.

T2 MC has detail-lacking encounter with someone from T1 where they reference “the past.”

There’s a couple things going on here. First, if the entire “tension” of your novel is the T2 sections withholding information about what happened at T1 and then letting it out in little dribbles, that’s not real tension and why are you even doing a dual timeline? T2 can’t be entirely filled with mooning about the past, but often it is because the author didn’t plan any meat for T2. A dual timeline novel should be a club sandwich, not one piece of bread looking mournfully through a window at a more interesting sandwich. Where this drives me absolutely crazy is when the book is in first person. Then you have a first-person narrator—which means we are essentially inside their head—which means the author has to do backflips to withhold information from the reader. As I have written elsewhere, withholding information is a cheap way of creating a mystery. So if nothing is actually happening in your T2 sections, people are going to be frustrated by their presence because they are standing between the reader and the T1 sections they want.

In some cases, you get 9/10ths of the mystery at T1 and that final cap in T2, towards the end… but is that enough to drag out the entire existence of T2? I tried to remedy this in two different ways. The first was having two separate mysteries. T1 is about something horrible these kids witness in 1995—then they spend all summer trying to figure out what it was and why it happened. T2 is about one of the six being murdered in 2015 and the remaining five having to solve the murder, and maybe solving the remaining 40% of the T1 mystery. You are (hopefully) invested in both, because both are meaty.

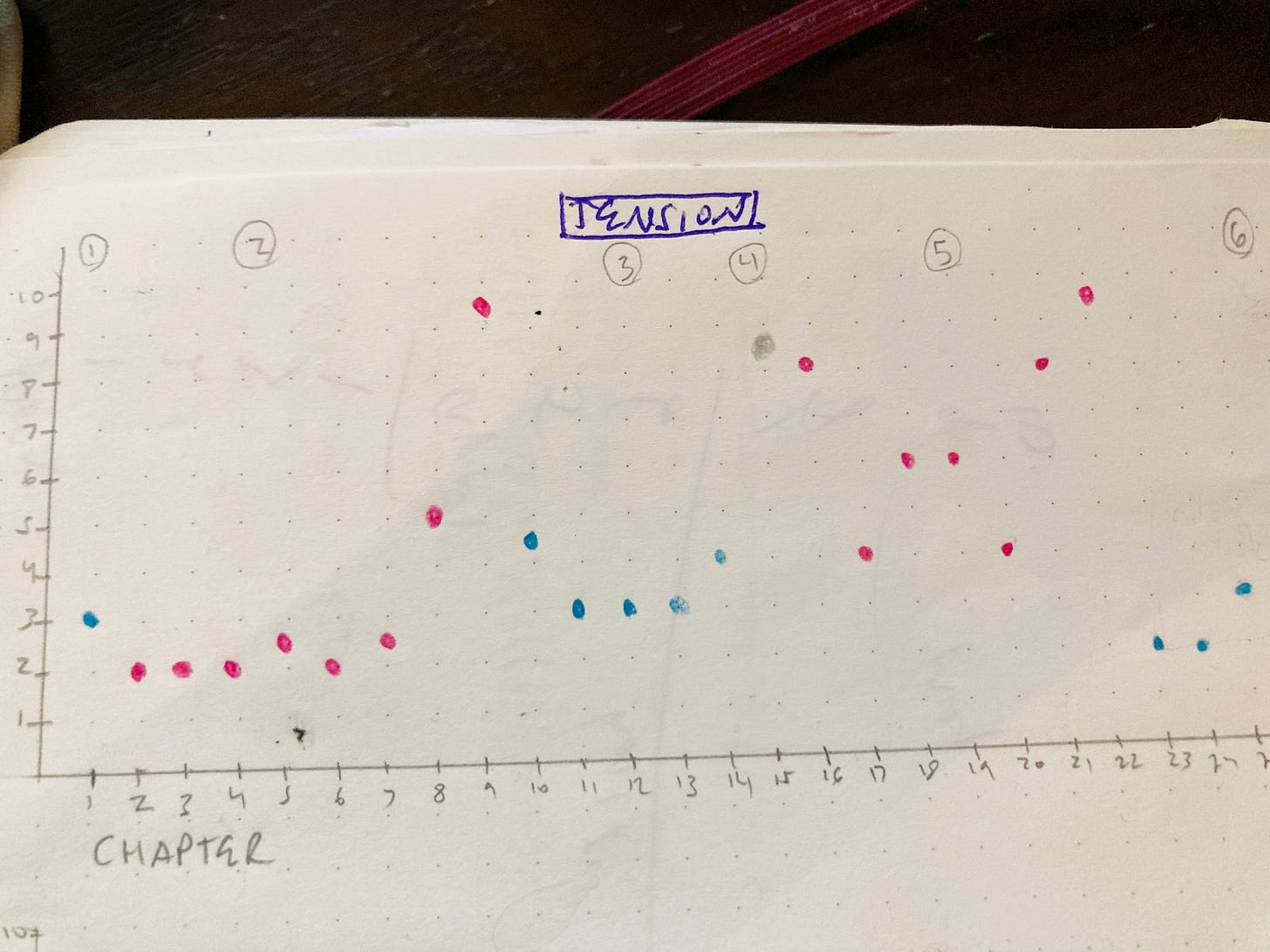

The second way I did that is by actually quantifying the pacing and tension. You can see a picture of this from my planning bullet journal.

The blue dots are 2015 (T2) chapters. The red dots are 1995 chapters. The Y axis is “tension.” Chapter 1: we introduce that someone has been murdered (T2 mystery) and that this must be connected to T1 mystery. Chapters 2-7 don’t have much tension because they are setting up the 6 main characters and building up the setting—which is really important in a book where the setting is like a main character. Chapters 8 and 9 are where the “horrible thing” happens. Then I drop you on your ass in 2015 with low tension, reintroducing the characters in 2015. The pencil mark for Chapter 15 involves a murder: you start the chapter knowing the POV character is going to be killed, but they don’t know that, only you know that. We’re cut off at that point in the photo, but I made sure that for each section, the tension rose across that particular section. The shapes are more dramatic for 1995, and I think that makes sense to me. Part of the drama I wanted to recreate from It was kids being in over their heads. Kids shouldn’t know how to deal with 9 or 10 tension.

The character development doesn’t ring true. My background is as a literary writer, so even if I’m reading smut, I’m thinking “where is the character development?” If I don’t care about your character in T1, I’m not going to care about them in T2. One of my pet peeves is when “character” = gender + looks + profession. As in “Lilly is just a mom raising her kids when something interesting happens.” Yawn. A bad dual-timelined novel will basically have the T2 character be their name + profession + trauma. Here’s the thing… none of those are a personality. Not everyone who survived 9/11 is the same or defines their life entirely around that event. The victims existed as real three-dimensional people before the attack, and maybe processed that event differently, and then they were three-dimensional people after the attack with the post being informed by the pre. Trauma is not a personality. Neither is a profession. I need to believe that someone was actually doing something with their life between T1 and T2. Even if they were emotionally scarred by it. People grow and change over time, even if their growth is stagnated by trauma, they don’t necessarily grow up but they grow different. (sidebar: this is the backbone to my objection to the recent Halloween reboot which is trashgarbage. I was mega excited to see that Jamie Lee Curtis had signed on to be in it, but was dismayed that the story line was “Laurie Strode was so traumatized by the events of Halloween that she spends the rest of her life obsessing over it.” Um, no? Not the Laurie Strode I know. Yeah, she would never forget it, but in my mind, Laurie definitely went to Vassar and became successful at something.)

When I was working on character development, when thinking about the 2015 versions of the characters, I thought not just about the effect of the 1995 events, but what their character arc would be overall as they reflected back on their childhoods and the passage of time. A few of them are reckoning with unhappy childhoods, and how they are building their lives as 30-somethings to contrast that. Some felt like they had something to prove in their professions. One is coming to a point where they’re realizing that it’s time to speak up for themselves—something they could never do as a child. They come back the same people, but different, older. I started thinking about this book just after I turned 40, which was a time when I really started to reflect on who I thought I would be back when I was a teenager, and how wrong I was, and what things I have made peace with, and what things I’m still struggling with.

Anyhow, if any of this has piqued your interest, this is a bit about my dual-timelined book.

There's something sinister under the surface of the idyllic, suburban town of Wesley Falls, and it's not just the abandoned coal mine that lies beneath it. The summer of 1995 kicks off with a party in the mine where six high school students witness a horrifying crime that changes the course of their lives.

The six couldn't be more different.

Maddy, a devout member of the local megachurch

Kelly, the bookworm next door

James, a cynical burnout

Casey, a loveable football player

Padma, the shy straight-A student

Jia, who's starting to see visions she can't explain

When they realize that they can't trust anyone but each other, they begin to investigate what happened on their own. As tensions escalate in town to a breaking point, the six make a vow of silence, bury all their evidence, and promise to never contact each other again. Their plan works - almost.

Twenty years later, Jia calls them all back to Wesley Falls--Maddy has been murdered, and they are the only ones who can uncover why. But to end things, they have to return to the mine one last time.

Thumbnail photo by Viktor Talashuk on Unsplash

This is SO helpful and omg I love your tension graph. Might need to start using something like that in my own projects. Thanks for sharing all this wisdom with us!

This is super interesting. I just wrote about using dual timelines, too— and it’s wild that I didn’t even notice til i read Vera’s piece that my A/now timeline is the one with my major dramatic question. B/past timeline has its own structure and set of beats (that I had to work really hard to pin down), but the big mystery is in the later timeline.

https://open.substack.com/pub/lauraleffler/p/dual-timelines-are-hard?r=1fisk&utm_medium=ios